News-Journal |

News-Journal |

Source: Save the Manatee

Club |

DAYTONA BEACH -- Manatees getting hit by boats in Florida may be grabbing most of the media attention, but the Sunshine State is not the only place in the world where sea cows face threats.

Outside the U.S., decades of hunting, entanglement in fishing nets and habitat degradation are claiming lives of these gentle marine mammals, and in some countries, such as Jamaica, scientists say manatees could soon become extinct.

"The underlying problem is human overpopulation," said Daryl Domning, professor of anatomy at Howard University in Washington, D.C., who spent several years in Brazil studying manatees. "There are just too many people everywhere."

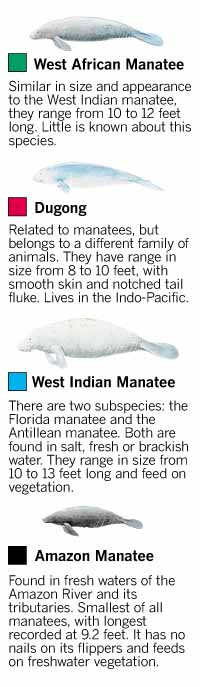

Three species of manatees live in the world: the West Indian manatee, which includes subspecies of the Florida and the Antillean manatee, the West African manatee and the Amazonian manatee. A similar animal called the Dugong lives in the Indo-Pacific region.

Most countries where manatees are found have protection laws that prohibit killing and hunting sea cows. Even in Jamaica, where there may be fewer than 100 manatees left, sea cows are considered endangered and have been protected since 1971.

Yet the biggest setback to manatee protection in countries of the developing world seems to be a lack of money for research and adequate law enforcement, Domning said. In Brazil, for example, thousands of miles of rivers are patrolled by a handful of wardens, he said.

In some countries, manatee meat continues to be sold, manatee researchers said. Sometimes, even local wildlife officials eat sea cow meat.

In parts of West Africa, for example, manatees are served as a main dish during special celebrations despite the fact they are fully protected, according to a report by James Powell, an aquatic conservation director for Wildlife Trust in Sarasota, who spent 10 years researching manatees in Africa. Local and federal wildlife officials are often invited to the manatee-eating festivities, Powell said in the report.

But while people in some impoverished regions of Africa see manatees as nothing more than a big hunk of meat, others consider manatees to be a water deity worth protecting, Powell said.

Some tribes in Senegal, Gambia and Mali, for example, developed traditions in which only certain hunters are allowed to kill manatees. Powell said it's usually a privilege passed from a father to a son. The killing of manatees is typically not allowed unless there's an extended ritual preceding the hunt.

Powell said many African tribes use manatees not only for food but for traditional medicine. Manatee oil, for example, is used to treat skin diseases and parts of the manatee penis are used to treat male impotency.

While manatees have always been an important part of life for some African tribes, Powell sees an increasing concern for manatee protection around the world.

"Twenty years ago, there was little interest for manatees outside of the U.S.," Powell said. "Now there's interest in almost every country manatees are found."

One of the most proactive countries in manatee protection is Belize, Powell said. Belize is one of the last strongholds of Antillean manatees, which are found throughout coastal and inland waterways of Central and South America.

Following Florida's efforts to protect manatees, the government of Belize instituted a network of manatee sanctuaries and established boat speed zones, Powell said. But unlike Florida, boat-tour guides lobbied for a lot of the manatee protections, he said.

"Guides in Belize see manatees as a large megafauna attractive to tourists," Powell said. "They greatly appreciate their natural resources because their income is associated with low-impact ecotourism."

Caryn Sullivan, a graduate student at Texas A&M University who's been studying manatees in Belize, said some fishermen and tour guides there slow down in areas where manatees are commonly found even when there are no official speed zones posted.

"It's done by common courtesy," said Sullivan, who is also a president and co-founder of Sirenian International Inc., a nonprofit grassroots network of manatee and dugong scientists, conservationists and educators around the world.

Despite the respect given to manatees in Belize, increased boat traffic claims the lives of at least one or two manatees each year, Sullivan said. Also, just like in Florida, many manatees have propeller scars, she said.

Manatees are also starting to get hit by boats in other countries with increasing traffic, such as Mexico and Costa Rica, scientists said.

As boat traffic increases worldwide, manatee experts said they hope Florida will serve as an example to many countries on how to protect manatees from boat collisions.

"Manatees in Florida are certainly best studied," Powell said. "If we can't protect them in Florida then I have little hope we're going to be able to do it anywhere else. We have the responsibility to maintain a leadership role."